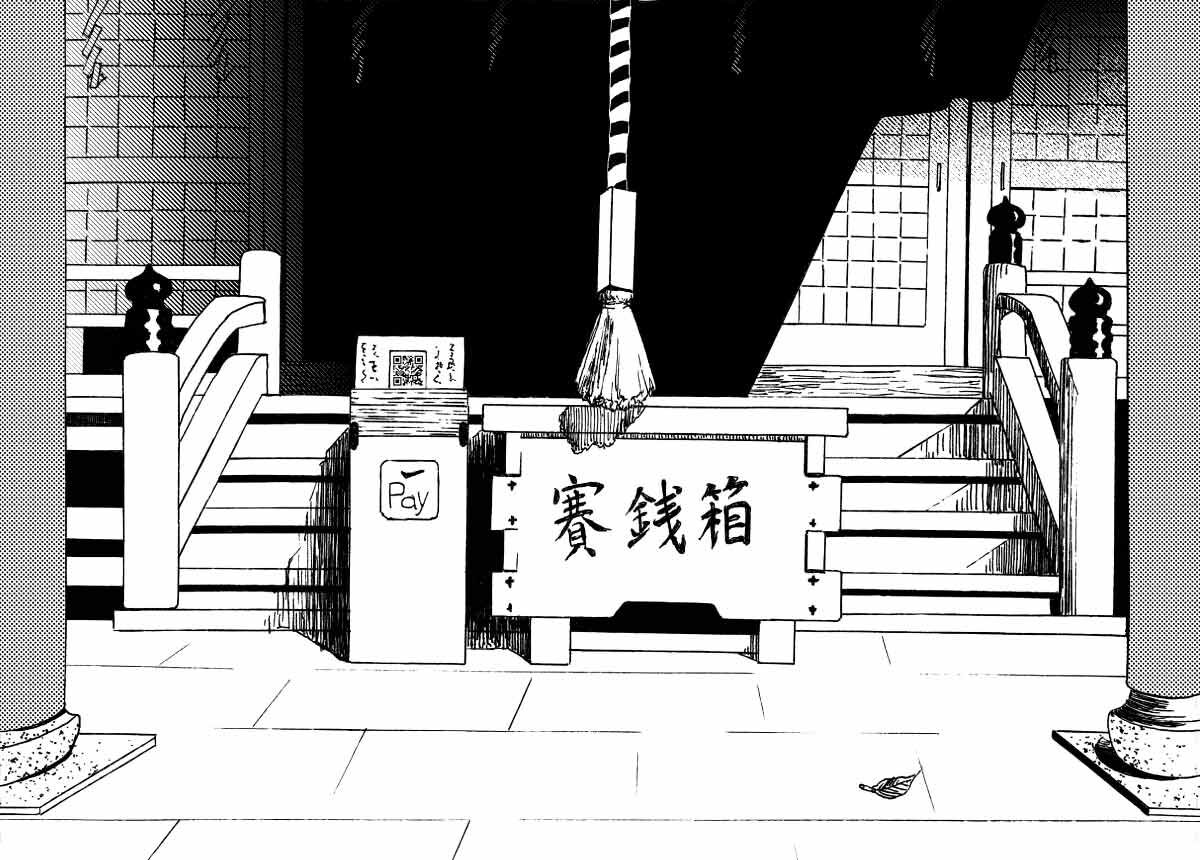

We go to a shrine and put offerings money. This is gratitude to the Deity. Originally, people offered rice and food from the sea and mountains in gratitude for the rich nature. Today, money is offered instead. The national average of it is $2.1 per person per year, according to the 2020 Survey of Living Attitudes.

Electronic money-offering has been spread at shrines and temples even before the January 2020 Corona expansion. For shrines, the advantages of e-money instead of cash include theft prevention, acceptance of foreign currency, and savings on coin-to-paper conversion fees.

But there is opposition on worshippers. A survey of 500 revealed a strong cash orientation, with 57% of them saying that cashless donations are “not good.” They said that they didn’t feel offering, that they might get them comeuppance, or that there might be system glitch or abuse. The Buddhist Association of Kyoto, which has the largest number of temples in Japan, is also opposed to electronic money-offering from the standpoint of “freedom of religion,” because of the fear that a third party may be able to determine where and how much a worshipper has paid.

Introducing e-payments is not as simple as posting payment codes at shrines. Religious organization are tax exempt in many items, and there are many legal requirements to receive new money, including cashless. If the act of receiving money from worshippers is considered a profit-making business, it is taxable, but if it is an offering (contribution), it is tax-exempt. Ultimately, the digitization of monetary offerings is related to the question of how shrines can clearly separate their revenue-generating business and monetary offerings for tax purposes.

The digital transformation in religion is gradually underway. However, it accompanies the problem of complexity of tax procedures.